Learn Git - Part 2: getting our hands dirty

This part is a direct continuation of Learn Git - Part 1: introduction, so if you haven't read it, go and read it first. We based on the things we learned and do there, so make sure you don't delete the repo we created in the part 1.

1. Making a difference

So, let's say Alice is just coming in and sat down in her work station, on the computer, she's on her local repo (a local copy of the repo of the project, in her own computer). Yesterday she made some changes to the LICENSE file, she wants to continue her work but don't remember the changes she made yesterday (so she don't remember where she's at).

To see the changes from the last commit, we can use the diff command. The output of the command is the changes that aren't in the staging area - changes to files the git system already track, but we yet to add them and include those new changes.

The "old" line will begin with a minus (-) at the start of the line, and the "new" line of code (with the changes) will begin with a plus (+) at the start of it. In our case the LICENSE file was empty, so we only see a plus line with the text we added to the file.

git diff

output:

diff --git a/LICENSE b/LICENSE

index e69de29..39604a4 100644

--- a/LICENSE

+++ b/LICENSE

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+Copyright (c) 2014 nirgn

If we now add the LICENSE file to the staging area and then run again the diff command, we'll see nothing (because all of the changes are added to the staging area), but if we ,nonetheless, want to see the changes even in the staging area we can use the staged flag and we would get the same output as before.

Don't regret anything! Ok, some things are ok to regret about

Now, if we use the status command, we'll see there is a file changed, added to the staging area, and ready to be commited. But if we didn't mean to add it to the staging area yet? What if Alice didn't finish with this file yet, and want add it to a different commit later on?

To remove files from the staging area we'll use the reset HEAD <nameOfFile> command. The elephant in the room - the HEAD in the command means the last commit in the current branch (timeline), in our case for the time being is main. So we actually reset the file to undo the changes, from the staging area, that were made until the last commit.

git reset HEAD LICENSE

output:

Unstaged changes after reset:

M LICENSE

Now if we run the status command, we can see that changes were made to the LICENSE file, but are not staged. If we want to undo the changes completely and revert the file to his state in the last commit we can do it by using the checkout <nameOfFile>.

git checkout LICENSE

output:

Updated 1 path from the index

Now the status command will show us there is no changes at all and the LICENSE file is back to his last commit state.

2. Revert all the things

Until now we regret adding files to the staging area, but what if we already commited the file? or maybe we forget to include something in the file and we want it to be in the same commit?

For those type of cases we can use the reset command with a new flag, soft HEAD^. This will undo the last commit, and bring all of the changes that were made in this commit to the staging area. As we said before the HEAD is the last commit in the current branch (timeline), but the caret symbol (^) says the one before. So HEAD^ means the commit before the last one, in the current branch.

So let's do some change to the README.md file, add it and commit it in one command (with a new flag). This type of add and commit is only allowed if the files is already been tracked. After we do it, let's use the reset soft command to undo it.

echo "This is a new line" > README.md

git commit -a -m "Modify README file"

output:

[master 017a141] Modify README file

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

$ git reset --soft HEAD^

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: README.md

Now we can still edit the README.md file and then commit everything together.

If you only want to add something to the last commit, and even change the last commit text, a simpler way is to use the commit command with the amend flag. It'll add everything in the staging area to the last commit and you can change the text of the commit in the process.

git commit --amend -m "Add a new LICENSE file and add text to README"

output:

[master 5870e6f] Add a new LICENSE file and add text to README

Date: Sat Oct 3 12:51:23 2020 +0300

2 files changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 LICENSE

Another flag to know it the hard, it'll undo the changes like soft, but instead of leave them in the staging area it'll delete them entirely like they never existed.

git reset --hard HEAD^

output:

HEAD is now at de7c8db Created an empty README file

The commit is just disappeared, our file revert to the commit before it, and the changes is not preset anywhere.

3. Can anybody hear me?

Until now, we worked on our local repo (the repo on our local computer). But what if we want to collaborate with another developer on the project? To do this, we need to upload the code to some sort of a server, if it's our company server or a different company server that we rent - doesn't matter, Bob (for example) need a copy of the code.

In the old times, like I wrote in the first post, we would probably transfer the code on a disk on key between computers back and forth. But now days, we'll sync our local repo with some server that'll host the project's code (another repository copy in another computer - a server, the cloud). In other VCS (Version Control Management) systems (like SVN for example) there is a centralized server - a single source of truth.

With git, every repo has it's own single source of truth. git makes it a bit difficult to create a single source of truth, but it's possible none the less. For most it'll be the server, and in particularly - GitHub.

This is where the push and pull commands comes in. Let's learn how to use them by creating a new repo on GitHub, and push our local repo to the remote repo on GitHub (that's why all of our commands will start with remote). First, if you don't have a GitHub account already, create one and verify it.

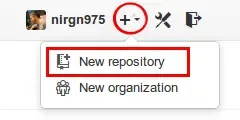

Now let's open a new repository by clicking on the plus button at the top right corner and then "New repository".

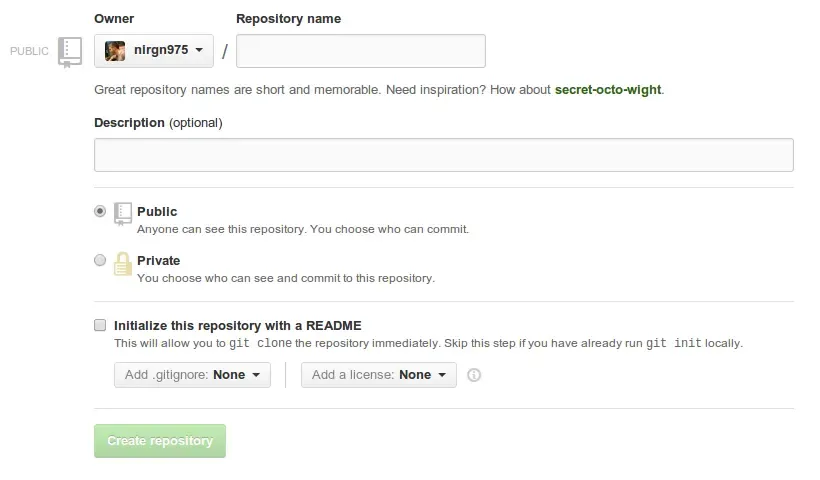

You'll be redirect to a new page where you can fill out all the details about the project, like the new of the project / repository, a description, make it public (free of charge, everybody can see the code and even fork it) or private and more stuff at the bottom - we'll not get in to it right now, some of it will be discussed in future posts.

In my case the name will be test, I'll leave the description empty, the repo will be public, and without README file, .gitignore or LICENSE files (we'll create the manually).

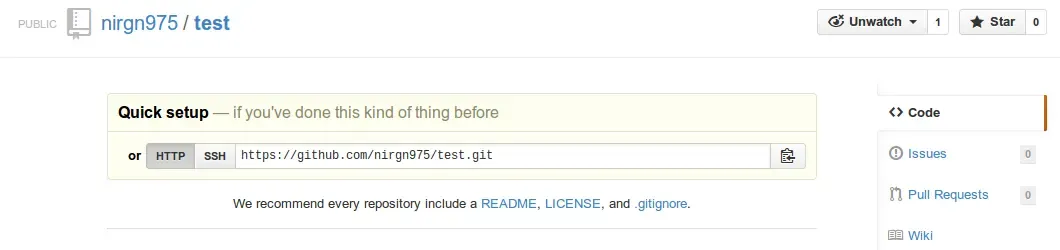

After we create the repo we'll get a URL from GitHub. This URL is the URL for the repo, with it we can push and pull code, and even clone the repo from GitHub server to a new local computer.

To push our code to the new GitHub remote repo we first need to config the GitHub repo address (the URL we got from them) as remote address so we can later push to that remote address. We'll do it with the remote add <aliasOfRemoteURL> <remoteURL> command.

git remote add origin https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git

git remote -v

output:

origin https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git (push)

I bet the first thing that comes to your head is "why we call our remote alias origin?", You're right, it's a bit wired, we can all if whatever we want. But origin is just a standard convention, and we'll love conventions. And the second command is just a way to print all the remote addresses, so we just make sure everything was added successfully.

Now, it's finally time to push our local branch (timeline) main to origin (the GitHub repo). You'll need to fill your username and password so GitHub will check if you have permissions to push to that repo.

git push origin master

output:

Enumerating objects: 3, done.

Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 224 bytes | 224.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To github.com:nirgn975/test.git

* [new branch] master -> master

If we refresh the GitHub repo page we'll see the README file there, and a new "Network" button (at the right menu, next to the "Settings") where we can see all the branchs and all the commits, with their messages, who're their author, when they commited, and more (basically like writing the log command on our terminal).

So, we pushed our repo to a remote source on GitHub (or any other git hosting), but how can Bob take this code to his local machine? Like we said before, with the pull command (we'll also use the pull command to sync our local repo with the remote one, so get changes other team members did and push).

git pull origin master

output:

From github.com:nirgn975/test

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up to date.

In this case, our local repo is already up to date with the remote one (of course it is, we push the code a couple of minutes ago and we don't have any one who push new code to our repo in the mean time).

4. Rap collaboration

A collaboration is an important thing, not just for open source projects where a lot of different people (maybe even from different countries with different time zones and languages) will work on the same project, but also at work, even if it's not a big company with a lot of teams, chances are you're not develop the software alone.

So, let's say Bob is working with Alice on the same team. It's his first day, and they want him to work on a new feature of the product. He need a local copy of the repo, so he clone the repo to his local machine. If you're on GitHub just go to the project repo and choose the "Code" tab, at the bottom (above the "Download ZIP") there is a section with the text "HTTP clone URL" - this is the URL of the repo, copy it, and then go to your terminal to clone the repo.

git clone https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git

The repo will be cloned on your local machine, in the directory that you were at in the terminal, to a new directory with the name of the of the repo. When you clone the repo to your local machine, the git system does 3 things:

- Download the repo to your local machine in a directory with the name of the repo.

- Add a

remotewith theoriginname that alias to the repo URL. gitwill configure a branch namedmainand point theHEADto be the lastcommitfrom themainbranch in theorigin.

5. Merge the branches

Bob is ready now to work on the new feature, but to do this it's better to create a new branch (timeline) and not to work on the same main branch of the project (main). This is because while he work on his own feature, other people working on theirs features or bugs too, and if everyone will work on the same branch and commit frequently, it'll create a mess, and everyone will "resolve conflicts" all of the time instead of working.

To create a new branch out (or splits if you want) of the main main branch (the current branch we're in right now) can be done using the branch command.

git branch home-page

After we created the new branch, let's check on which branch we're in right now.

git branch

output:

home-page

* master

We're still on main. So to move to the home-page branch, we'll use the checkout command.

git checkout home-page

output:

Switched to branch 'home-page'

Now we're in a different timeline (branch), we can do whatever we want and it'll just do it just in the home-page branch, and nothing will infect our main branch. Any time we want to can go back to main branch, and see the repo from main branch point of view (timeline).

In the meantime, while we work on our feature, if other members of the project finish their own work and merge it to main, we can always checkout back to main, and pull the new commits in main, to see our coworkers job.

Now that we're on a new branch (home-page), let's create a new file called index.html, inside of it we'll add the basic html code we need for a simple web page, add it to the staging area, and commit the file.

$ touch index.html

$ echo "<html>\n\t<head>\n\t\t<title>website title</title>\n\t</head>\n\t<body>\n\t\tcontent of website ...\n\t</body>\n</html>" >> index.html

$ git add index.html

$ git commit -m "Add basic html code"

The commit we just did, will be added to the current (home-page) timeline (branch), and will not be seen in any other branch. If we write the ls command in the terminal (in the current directory) we'll see all of our project files (README.md and index.html), but if we'll checkout to the main branch we'll not see the index.html file, even if we write the git log command, we'll not see our latest commit in there.

Let's just check we aren't crazy and checkout back to the home-page branch, and then with the ls command makes sure we see our index.html file.

So, let's say we're done with this task, we did all of the things we had to do here and we're ready to merge this home-page branch to the main branch. To do this we're first need to go to the branch we want to merge things to (in our case main), and then use the merge command to actually merge the code from the other branch to the branch we are at right now.

git checkout master

output:

Switched to branch 'master'

and then

git merge home-page

output:

Updating de7c8db..bfb8f2b

Fast-forward

index.html | 8 ++++++++

1 file changed, 8 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 index.html

We can see that git tells us it's update the branch by "Fast forward", but what is it means? it's when we try to merge one commit with a commit that can be reached by following the first commit’s history, git simplifies things by moving the pointer forward because there is no divergent work to merge together, so it's called "fast-forward".

When we finished mergeing the branch, we don't need it anymore, so we can just delete it. We'll use the branch command with the d flag to do it.

git branch -d home-page

output:

Deleted branch home-page (was bfb8f2b).

Now let's create a new branch to work on a new task, the branch will be called basic-main (because we'll add some basic code to the main website page - index.html). We can create the branch and then move to it in two separate commands like we did before, but there is a simpler way! We can use the checkout command with a flag (b) that tells to create the branch if doesn't exist yet, so this way, in one command we create the branch and then move (checkout) to it.

git checkout -b basic-main

output:

Switched to a new branch 'basic-main'

Then we'll add the <a href="detailed.html">Go to detailed page!</a> line right after content of website ...

<html>

<head>

<title>website title</title>

</head>

<body>

content of website ...

<a href="detailed.html">Go to detailed page!</a>

</body>

</html>

Now we can commit the change in index.html and create a new page, detailed.html that the link will redirect us to (when we click it).

git commit -a -m "Add a link to detailed page"

output:

[basic-main e979b01] Add a link to detailed page

1 file changed, 7 insertions(+), 6 deletions(-)

and then

touch detailed.html

echo "<html>\n\t<head>\n\t\t<title>website title</title>\n\t</head>\n\t<body>\n\t\t<h1>This is the detailed page<br><form><input type='button' value='Go back!' onclick='history.back()'></form></h1>\n\t</body>\n</html>" >> detailed.html

git add detailed.html

git commit -a -m "Finish detailed page"

output:

[basic-main af3853e] Finish detailed page

1 file changed, 8 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 detailed.html

Let's imagine how our repo branches (timelines) is looking right now.

gitGraph: options { "nodeSpacing": 100, "nodeRadius": 10 } end commit commit branch basicmain checkout basicmain commit commit

Right in the middle of our work on the basic-main branch, we get an email from our boss that there are bugs in main and we need to take care of it immediately. So let's head over to main (you can run git branch after you checkout to main just to make sure you're on main).

git checkout master

output:

Switched to branch 'master'

We don't know if anyone of our team members done with their work and merge it to main while we worked on our feature branch, so let's make sure we have an updated main by pulling any new commits from origin. Let's fix what we need to fix, and commit and push it to origin.

git pull origin master

output:

From github.com:nirgn975/test

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up to date.

then

echo "# Awesome Website\n\nThis is the repo for the awesome website" >> README.md

git commit -a -m "Add a description for the repo"

output:

[master c247760] Add a description for the repo

1 file changed, 3 insertions(+)

and finally

$ git push origin master

output:

Enumerating objects: 7, done.

Counting objects: 100% (7/7), done.

Delta compression using up to 16 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 679 bytes | 679.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

To github.com:nirgn975/test.git

de7c8db..0baa97a master -> master

Now that we put out the fire, let's head over to our basic-main branch, finish the work, commit it, and head back to main to merge it.

$ git checkout basic-main

output:

Switched to branch 'basic-main'

then

sed -i '' "s/content of website .../Welcome to the new website/g" index.html

git commit -a -m "Change welcome message"

output:

[basic-main a0ff187] Change welcome message

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

then switch branches

git checkout master

otuput:

Switched to branch 'master'

and finally

git merge basic-main

output:

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

detailed.html | 8 ++++++++

index.html | 13 +++++++------

2 files changed, 15 insertions(+), 6 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 detailed.html

After the merge command a VI editor will open up on you terminal. With this, git is basically telling us I made the merge commit for you, but if you'll need to be more specific with the commit message edit it (and there is a default commit message in the Vi editor). To exist the VI editor we'll write and quit (:wq).

Because we merge two branches with changes in each of them, git is doing a "recursive" merge - git create a new commit right where we merge them, we can see it with the git log command.

Let's imagine how to whole process looks like visually.

6. Q & A

It's time to practice. Remember that the best practice is through your fingertips. If you don't have a project you want to upload and share, just create an empty directory and put a simple text file in there. If you can't figure out something, it's okay to look at the answers, but don't just look at it, write it in the terminal (don't copy-paste, write it on your own).

Questions

- A new file was added to the project, write a command to show you the changes from the last

commit. - Add the

index.htmlfile to the staging area. - Wait a second, a colleague walks by your desk and ask to see what is different from the last

commit, show him. - The colleague updates you that this

index.htmlis no longer relevant, delete it from the staging area. - Do some changes to the

README.mdfile, and becausegitalready tracks that file,addandcommitin one command. - Oops! I forget to tell you to add another file to that

commit, you need to create a new file namedmap.indexandcommitit with theREADME.mdfile from the last commit. - Wait I didn't tell you what content to add to the

map.indexfile, return it to the staging area. - A colleague send you in an email the new repo URL, add it to your local repo configuration (it's:

https://github.com/example/importantProject.git). - You're done for today, let's push everything to the remote repo. Use a special flag so you'll not need to write the

originalias next time. - The IT team has wipe out your hard disk by mistake, clone the repository to your local machine from the address https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git

- We need to create a new branch (with the name

fix457) to fix some code, create it a move to it in one command. - Merge the

fix457branch to the current branch you're in right now.

Answers

- The

git diffcommand. git add index.html.- Use the

git diff --stagedcommand and flag to show the changes that were also added to the staging area. - The

git reset HEAD index.htmlcommand. - Use the

-aflag like so:git commit -a -m "Modify README.md file". - Because

gitdoesn't track the new page let's first add itgit add map.index, no we can use the-amendflag to add it to the last commit:git commit -amend -m "Modify README.md file and add map.index". - Use the

git reset -soft HEAD^command. - Use the

remote addcommand like so:git remote add origin https://github.com/example/importantProject.git. - You need the

pushcommand with the-uflag:git push -u origin master. - Use the

clonecommand like so:git clone https://github.com/nirgn975/test.git. - Use the

checkoutcommand with thebflag, like so:git checkout -b fix457. git merge fix457.

7. Summary

We now know how to see the changes that were made from the last commit, how to go back if we regret something we did in a commit or the commit message, or even forget to add something to the commit.

We upload the project to a remote repository (GitHub in this case), we created new branches, worked with other team members, and merge our code to the main branch (we go over a merge with no changes in main and with one with changes in main, but not in the same file - we'll talk about it in future chapter).

We definitely learned a lot in this chapter! Don't forget to practice it through your fingers, it's the best way to learn something new. And don't hesitate to ask questions in the comments if something is not clear - I'll do my best to help.

📖 You might also like

Change your email in GitHub

Once in a lifetime a man changes his email address. Maybe you didn't changed your email even once, I completely understand you, but I did. And let me tell you - it's not an easy process!

Crack The Hash

In earlier post (at Passive.. Passive Recon.. Passive Reconnaissance.. OSINT!) I mention we can use hashcat to try and crack a password we found, but it wasn't the meaning of the post (and it's a red line for me to do that and put his cleartext passw