Learn Git - Part 1: introduction

I think everybody here at least heard about GitHub and maybe even about the file management system called git which is everywhere in the development world those days. So, as a computer science student I choose to learn it, and what batter way to learn something then to write about it.

So in this series of posts I'll document my journey to learn git (which is the base of GitHub as the only version control you can use on the platform). I hope more people can use it as a learning document or even to deepen their knowledge in the tool.

1. Some General Knowledge

git is a distribute version control (basically a file management system with a db to save the changes that were made to those files over time) created by Linus Torvalds in 2005. Why he even created it you ask? He and some other Linux Kernel developers weren't happy with the source-control management (SCM) software they used at the time (BitKeeper). You can read in the Wikipedia page of git about what exactly their issues was, but this is out of the scope of this post.

Why I even need a source control system?

This is a valid question. In the old days you were just edit your code, FTP it to your server, and that's it. Maybe you have one more fellow developer with you on the same project, he would have send you a piece of code, you paste it in the exact location in the file he told you too and that's it - FTP it to the server.

You had problems? just shout him a question he probably down the hallway. But when software started to eat the world, getting bigger, more complex, with bigger teams, in different places in the world and different time zones it started to get messier. You need a version control to manage the code in different computers, try to merge pieces of code together, save the history (the changes that were made so we can go back in time in case we encounter some issue), and even want to know who made those changes.

How GitHub is related to all of this?

GitHub is a hosting company for git (repositories). The service was founded in 2008 and hosts public repos for free and private ones for a fee. But, from that simple idea, GitHub built a fully fledged software management system, it's now basically a way to manage the whole project with some social media capabilities and a way to share and contribute code.

2. Simple Commands

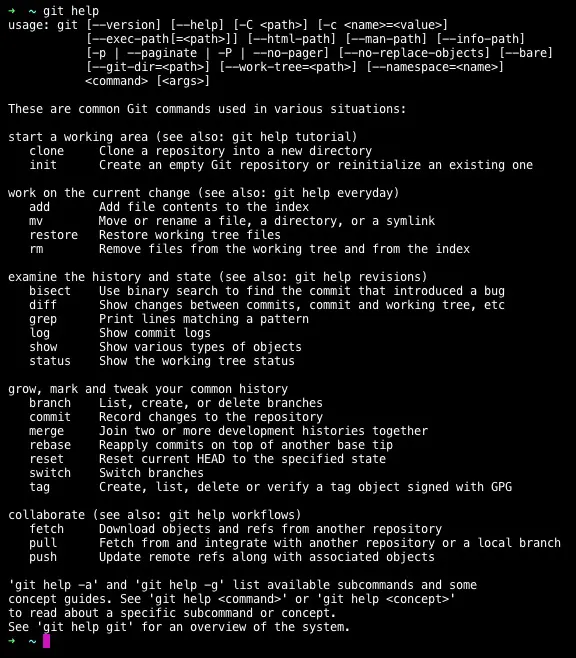

Like most of CLI (command line) tools, git comes with a help command. So, if we ever got stuck we can always use it to find out about some command.

git help # print all the commands with a simple explanation.

git help config # print all the config command options with a simple explanation.

To install git I'll use brew (on Mac), but it's pretty easy to install on any OS, just use this guide for you OS. After we installed it, the first thing we want to do is to set our username and email, so every commit (we'll get to what is commit in the future) will be belong to you.

brew install git

git config --global user.name "<YourNameHere>"

git config --global user.email "<YourEmailHere>"

We're ready to start working on our first repository (repo for short). Let's create a new one (just navigate to your wanted location in your file system with cd) and then initiate a new repo (you can do it with an empty directory or with a directory with some files in it already). This will create an invisible directory (directory that start with a dot (.)) with the name git.

cd projects

mkdir newProject

git init

Now we have a local repository (not on any server, local to your computer).

3. Workflow

Before we continue diving with the tool, I would like to take couple of minutes to go over the workflow with git. For convince I would borrow some names from the cryptography world: Alice and Bob. Let's suppose Alice created a file README.md and when a new file is created, it's start his life as an untracked file (that's means that the git system doesn't know about it), to make git` track this file we need to add it to the _staging area_, and finally we make a commit- that's agit` command to take a snapshot of all the files in the _staging area_.

Now let's assume Alice working some more on the README.md file, doing some changes and even add a new file LICENSE`, when she done, she need to add both of those files to the _staging area_, again, and commit` those changes. This is pretty much will be our workflow at the moment. We'll making some work -> add the work that we done to the _staging area_ -> and commit it (taking the snapshot).

4. More Commands

Once we understand the workflow in theory, we need to practice it.

Maybe the most important command in git (in my opinion) is status - it allow us to check the changes that were made from the last commit (snapshot). Let's see what the result of this command will be after we initiate (with git init) the repo, and created a README.md` file (didn't nothing like adding it to the _staging area_ or commit` it).

git status

output:

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README.md

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

We can see we got couple of pieces of information back:

- We are on branch

main(we'll take about branches later) - There is no commits yet in this repo.

- We have a new file (file that

gitdoesn't track) in the name ofREADME.md - Nothing was added to the _staging area_, and `git` knows that there're files that it doesn't track yet (so we have something to give him, to adding to the _staging area_).

So let's give git what it wants, let's start tracking this README.md file (with the add command and right after it the file itself), and then do another status command to see the output now.

git add README.md

git status

output:

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README.md

We see almost the same pieces of information, but now git` have a file in his _staging area_ (a file ready to be commited). So, it's time to do our first commit. To do this we'll use the commitcommand. A flag that thecommitcommand have ism` which means _"message"_, with this flag we can add a message to the commit to describe the changes this commit is do.

When we do the commit we basically take a snapshot of our file system in this exact time. Even a space means a change. This commit is added to the repo (project) timeline (it's accepted to draw it and imagine it as a timeline, because every commit has a timestamp, so we can place them all on a big timeline from the start of the project until now).

git commit -m "Created an empty README file"

output:

[master (root-commit) de7c8db] Created an empty README file

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 README.md

if we write the status` command again, we'll see there is no changes to be added to the _staging area_ or no changes in the _staging area_ to be commited. We also can see in the first line that we on branch main, for now everything you need to know on branches is that we have a timeline (branch) in the name of main, and we commit` things to that branch (timeline).

git status

output:

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Now let's make some changes in README.md and create a new file named LICENSE (like we said Alice did in the workflow section), and run the status command again.

echo "first change" > README.md

touch LICENSE

git status

output:

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: README.md

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

LICENSE

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git knows that the README.md` file has changed! and those changes are not staged (not in the _staging area_, not ready to be commited). git also noticed we created a new file that it doesn't track (LICENSE`).

To commit those files we need to add them to the _staging area_ first, we can do it like we did it earlier with the add command and the two files (with a space between them), but we can do it more efficiently with the `all` flag - which will add all of the changes and untracked files to the _staging area_ (be careful with this flag because something you).

After we add them, we can use the status` command again to see what have changed. We can see we have two files in the _staging area_, ready to be commited, one (LICENSE) is a new file, and the other (README.md`) is a tracked file that just changed (modified).

git add --all

git status

output:

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: LICENSE

modified: README.md

Now let's do a new commit (take a second snapshot) and then explore it a little bit.

git commit -m "Add a new LICENSE file and finish README"

output:

[master 380c1e1] Add a new LICENSE file and finish README

2 files changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 LICENSE

To look at the history, the log, of the current timeline we can use the log command. We see there're two commits in the branch (timeline) we're currently at. And also much more information:

- We're in the

mainbranch (timeline). - The

commits hash, which is a unique string of number and letters to represent thatcommit. It's basically the name of thecommit, with it we can reference thatcommit. - The author and the exact time and date of the

commit. - The message of the commit (this is why the message is important. It should be understandable, concise and describe exactly what the changes are. It also accepted to write in present time and not history or future).

git log

output:

commit 380c1e1346008245c8268ccb039538df3e314b87 (HEAD -> master)

Author: Nir Galon <nir@galon.io>

Date: Sat Oct 3 12:51:23 2020 +0300

Add a new LICENSE file and finish README

commit de7c8db1ce767a3a757d760cb7200abe9d847c65

Author: Nir Galon <nir@galon.io>

Date: Sat Oct 3 02:03:24 2020 +0300

Created an empty README file

Like the drawing below, we can imagine it as two dots, where each dot is a commit (snapshot), and a line (timeline, the branch) is connected them. Going from the first (oldest) one at the left, to the newest one at the right. Where the most newest commit, the dot to the most right, is our current commit (HEAD).

gitGraph: options { "nodeSpacing": 150, "nodeRadius": 10 } end commit commit

5. Q & A

Let's practice a little bit by going over the things we learned.

Questions

- You want to initiate a new repo. You're already in a directory with a file, what command do you write to do it?

- You created some files, made a few

commits, you updated some files and the day is over, you want to do your lastcommitfor the day and go home. But you don't remember what files you have changed from the lastcommit, what command can help you see the changes from the lastcommit? - You found out with the last command that you have only one file changed (

index.html), make him ready to becommited. - Make a

commit. - You created a new directory (`css`), with couple of files, add the entire directory (with all of it's files) to the _staging area_.

- A colleague goes by your desk and ask you what have you been

commited today, what command do you write to show him?

Answers

- The

git initcommand. - The

git statuscommand. - The

git addcommand:git add index.html. - The

git commitcommand:git commit -m "Add index.html". - To add an entire directory we'll just write it:

git add css. - The

git logcommand.

6. Summary

So, we learn a bit about the history of git, why do we need it and how GitHub is related. From there we move on the learn some basic commands, the git workflow, and then to some of the most used commands in git.

I recommend to learn through your fingers - to write all the commands yourself and see the output in your terminal. This is the best way to learn! Don't copy and paste answers to your terminal, write them yourself, slowly it'll get through and you'll remember and understand it all in no time.

📖 You might also like

Change your email in GitHub

Once in a lifetime a man changes his email address. Maybe you didn't changed your email even once, I completely understand you, but I did. And let me tell you - it's not an easy process!

Crack The Hash

In earlier post (at Passive.. Passive Recon.. Passive Reconnaissance.. OSINT!) I mention we can use hashcat to try and crack a password we found, but it wasn't the meaning of the post (and it's a red line for me to do that and put his cleartext passw